CAP Prize 2021 | Shortlist

CAP PRIZE 2021 | SHORTLIST

These 25 shortlisted artists – in alphabetical order – were chosen from approximately 800 applications to the CAP Prize 2021 by a panel of 21 international judges. The shortlist comprises works by: Aàdesokan | Yetunde | Ayeni-Babaeko | Thami Benkirane | Marcus Trappaud Bjørn | Nabil Boutros | Katel Delia | Justin Dingwall | Andrew Esiebo | Jason Florio | Pippa Hetherington | Brian Hodges | Eldin Zainab Imad | Matt Kay | Adil Kourkouni | Tamary Kudita | DeLovie Kwagala | Dillon Marsh | Fabrice Monteiro | Claudia Ndebele | Emeke Obanor | Joseph Obanubi | Léonard Pongo | Mahefa Dimbiniaina Randrianarivelo | Paul Shiakallis | Mauro Vombe

Aàdesokan

Born in 1994 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives in Amsterdam, The Netherlands

www.aadesokan.com

Instagram: @manqbt | Twitter: @ManQBT

Waste Identity: Passport for Plastics, 2019

Untitled

Waste identity is an imaginary theorization, fixated on the relationship between waste and identity, to discover the feasibility of negotiating usage of the identity of waste as a metaphor for displacement and human migration. It acts as a method for the construction of consciousness, a consciousness of the visceral relationship plastic waste has with human migration.

The migration of people interplayed with the movement of waste shows that human migration is inhibited by borders, but waste moves freely, goes everywhere and anywhere, like a stretched parchment distributed all over our societal landscape, unaccountable. Its identity is interchangeable with human identity, plastic waste is prominent in our collective identity yet we hardly consider our waste Identity.

Using waste as a vehicle to explore broader social and political dynamics, will there be urgency if waste is treated like an immigrant in its movement? Would we then react differently to the movement of people? The International Passport acts as a placeholder for identity, it holds space and informs identity. Our waste identity faces no restrictions in its movements, it travels unhindered. Plastic waste is a huge part of the world population, perhaps issuing passports for plastics can check this flow since passports discriminate against the holders from entering and leaving a territory.

As an individual, I cannot move as freely as the waste I generate. We are in a reality where our waste travels the world freely, without being subject to scrutiny or suspicion. My waste identity allows me endless movement, it allows me privilege to move, perhaps in embodying this identity, the world would be fluid and permeable to me, I can go anywhere and everywhere, traveling far and wide, to the remotest places, unchecked, unhindered…

Yetunde Ayeni-Babaeko

Born in 1978 in Enugu, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.yetundeayenibabaeko.com

Instagram: @yetundeayenibabaeko_photo

Persons with Albinism - White Ebony, 2019

Twins

The first time I saw an Albino was in Nigeria. Or maybe I had seen one in Europe before, but let us say the first time I recognized an Albino as one was in Lagos.

Among all the black people, the yellowish-white skin color of the Albino truly stands out.

Immediately I felt some kind of connection cause here was another person, who like me, did not have the right skin color to blend in.

But this is where the similarities between me and Albinos end. Through my work with PWAs (Persons with Albinism) I have learned a lot. I have learned that standing out because you are from a different country is one thing. But being born, bread and being the same with people who now actually discriminate against you, is another.

Nigeria is the PWAs country, their families are Nigerian, they speak, breathe and live the culture, but still they feel as if they are not entirely part of the whole thing. Moving forward is hard, but going anywhere else is not an option. In my work, I want to discuss the struggle of the Albino. I want to encourage the viewer to look deeper into the subject, as I have also discovered that not many Nigerians have actually engaged themselves with the topic of Albinism. In the images with the zipper the PWAs are reminding you that they are Africans through and through, hidden under a skin that simply lacks melanin. My images also remind you of paintings of the Renaissance or Baroque epoch. That is due to the lighting, accessories and editing. Here I intentionally borrowed from The Great Painters to keep the discussion going. PWAs, due to their light eyelashes and eyebrows, always remind me of the kings and queens in the paintings of the great renaissance artists.

Thami Benkirane

Born in 1954 in Fès, Morocco. Lives in Fès, Morocco

Facebook: Thami Benkirane

White Writing, 2020

Untitled

The experimental photographic series entitled "White Writing" attempts to capture a fleeting phase in the movement of one or more people walking. The series also includes animals (cats, dogs, birds).

This phase captured in the dynamics of walking is revealed by a partial or total doubling of the subject. This double is revealed as "negative" on the photographic plane. The white silhouette does not correspond to the shadow cast. It is thus manifested directly during the shooting by the use of long exposure times and overexposure (between 2 and 3 EV: Indices de Lumination). The digital camera is used without a tripod and with all image stabilisation modes disengaged. Since the sharpness of the image is not the ultimate goal, a voluntary shaking of the camera accompanies the moment of shooting.

In the history of our medium, this experimental series is reminiscent of the experiments that established chronophotography (cf. Eadweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey, etc.).

The difference is that in the present series, the dynamics of walking - captured as a palimpsest of steps and gestures - is captured in the same photographic shot by means of a single photograph. It is a kind of instantaneous chronophotography.

In resonance with the history of art and through its interest in the capture of movement, this experimental series is similar to the concerns that animated Futurism, an artistic movement of the early 20th century.

Marcus Trappaud Bjørn

Born in 1987 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Lives in Copenhagen, Denmark

www.marcusbjorn.com

Instagram: @marcustrappaudbjorn

Onchocerciasis, 2019

Buba Ali

Onchocerciasis is marked by Marcus' use of a fundus camera. A camera which is normally used in eye clinics and hospitals to examine diseases such as glaucoma and diabetes and which makes it possible to photograph the retina of the eye.

Travelling by small aircrafts, pick up trucks, motorbikes and canoes he managed to bring a 30 kg fundus camera, to the remote Community of Gangumi in Taraba State, Nigeria.

In Gangumi he used the unintentional aesthetics of the fundus cameras for a disease that the technique is normally not intended for. He enables us to see beyond our eyesight and allows us to look through the pupils of the people suffering from onchocerciasis. The result is a terrible disease rendered into beautifully planet-like pictures of different colours.

Onchocerciasis is spread by the black fly, which lives near the fast flowing rivers in the rural parts of Africa. When bitten by the fly, a worm larva enters the body where it produces thousands of microfilariae that invade the body and travel toward the eyes causing severe damage to the retina. It is particularly prevalent in Africa, where more than 99 percent of all cases occur. 500.000 people are already blind, 37 million are infected and another 120 million are at risk. Still this devastating disease is almost unknown to the western world.

Nabil Boutros

Born in 1954 in Cairo, Egypt. Lives in Paris, France

www.nabil-boutros.com

Obscure Object, 2020

Obscure Objet 01

Why are some women veiled and others not? A simple question that worried the teenager I was – in Cairo’s seventies – and never left me.

Over time, I heard all kinds of answers, more or less convincing. Some fell within the religious precepts, others were about morality, others of custom, when the three are not confused… With the resurgence of fundamentalist trends in recent years arguments have been exacerbated.

Among other arguments there is: A woman is a temptation that man must be preserved from. Also: You cannot let your own treasure be revealed to strangers’ eyes. Statements set out by men but also defended by women.

These answers have begotten other questions:

Why should women be veiled and hidden to men’s desire?

What about women’s desire?

Could this be a confession that women have a better control of their drive while men are but beasts that cannot escape from it?

Either: Between meen and women, does the haggled marriage eliminate the seduction?

What about power relations and property?

Do honour matters bring a guarantee to men that their offspring is actually from their "juice"?

In fact, historically, the three monotheistic religions have integrated an Assyrian law dating back four thousand years, which required that prostitutes had to be bareheaded when they were out. They were severely punished if they did not conform to it. The sliding to a reversed meaning is easy to observe. The power relationship had been specified a little bit more in these faiths, since the woman is fashioned from a curved bone from the Man, moreover, of little importance: a coast!

Together these three religions are the majority on earth. Then by irony, I return the argument by veiling men who would be irresistible temptations for the women and to avoid them to fall in sin.

I therefore designed this series of images of attractive but veiled young men, posing following the example of the feminine fashion magazines.

Katel Delia

Born 1975 in Thiais, France. Lives in Paris, France

www.katelia.com

Instagram: @artkatelia

Entre-Temps. De Malte à Tunis, 2019

Untitled

A photo lives through different times, every time differently. At the time they were taken, they were important, then they were kept, looked at, forgotten, finally rediscovered.

My Maltese father’s family has kept many pictures of their time in Tunisia, after emigrating from Malta. For me it is a sign that they wanted to preserve the memory and to transmit it. The Maltese of Tunisia are forgotten, and I would like to give them a place in history through these family photos. They are much more than most people think.

I established a connection with the places and the streets of Tunis, La Goulette and Le Khram. I reclaimed them, together with the memories giving them a universal sense.

What did I inherit from this period, from the 1930s to the 1960s? Can we be nostalgic for a place, an atmosphere we have not experienced?

More than a century ago, Maltese fled poverty to join Tunisia, a land of promise for a better future, today crossing is the other way…

Justin Dingwall

Born in 1983 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

www.justindingwall.com

Instagram: @justin_dingwall

A seat at the table, 2018

Ruby II

I worked with the old saying “a seat at the table” to represent the idea of an opportunity to be heard, to be seen to have a voice and an opinion, and in this way to make a difference.

The images that I have created with Moostapha aim to start conversations about preconceived ideas and perceptions based on appearance and how what we see affects what we think.

There are some main aspects of symbolism that are important in the work. I was especially interested in using everyday objects. I like to reinterpret these objects by slightly altering their appearance and presenting them in new ways to the viewer. What I have found very interesting is how people react to these everyday objects once they have been altered and used within the imagery. Everyone interprets their own significance based on their own experiences - be it positive or negative.To adapt an old saying: art is in the eye of the beholder. Viewers bring their own experience and perceptions to the work, and that is what I aim to achieve, for the topics to be openly discussed and brought into everyday life.

The reason for the precious stones on Moostapha’s skin in five of the artworks, came from the discussions that Moostapha and I have about his life and how the world perceives him as a person living with vitiligo. He has told me on a few occasions of how people stare and point at him for being different. I have also used the images of thousands of eyes to be a representation of society and how we stare at someone when they look different, when people do not fit into our preconceived ideas. In our conversations I learnt that it was very difficult for Moostapha growing up, but through these challenges he has gained strength and confidence from looking so different. He no longer sees his vitiligo as a hindrance, but as something precious and unique. In these images it is now Moostapha who is staring back at the viewer. Questioning our gaze.

Andrew Esiebo

Born in 1978 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives in Simawa-Ogun, Nigeria

www.andrewesiebo.com

Instagram: @andrewesiebo | Twitter: @andrewesiebo

Coro Angels, 2020

Mariam Abdullahi

During the first wave of the coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria I collaborated with the Nigeria Center for Disease Control to document Nigeria’s response to the global pandemic, particularly the activities of those on the frontline of the fight against COVID-19.

Facing up to this invisible enemy has been an unimaginable struggle for many of the workers, who endure everything from inadequate resources to poor welfare and the social stigma of working with coronavirus patients. Yet they remain unfazed, putting their lives on the line day after day to help Nigeria overcome this global pandemic.

Very early on in the crisis, I myself caught the coronavirus and while I was able to recover at home, I saw first-hand – not just as a photographer, but as a patient – the enormous challenge facing Nigeria’s health services. Therefore, I am using this to pay homage to these ‘angels’ and to shed light on some of the experiences that shared with me.

In the line of duty caring for and protecting victims of the virus these ‘Coro Angels’ (‘Coro’ is the colloquial term for coronavirus in Nigeria) have been kitted out with personal protective equipment, which renders them faceless. As a result, the personal sacrifice of individual workers like nurses, doctors, healthcare assistants and lab technicians is rarely acknowledged.

It was important for me to photograph them before they went ‘into battle’. Placing a halo of colour on the walls of the spaces where they performed their duties reflects their sacred role and sacrifice. When wearing their PPE, we can see the effort and discomfort they undergo to wage this war against an invisible enemy.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with an ongoing and even deadlier second wave of the virus, my prayers and sincere gratitude goes out to Nigeria’s ‘Coro Angels’ and I echo their calls for the general public to play their part in controlling this pandemic with social distancing, regular hand washing, the use of face masks and hand sanitizer.

Jason Florio

Born in 1965 in Kingston, United Kingdom. Lives in Cape Point, Gambia

www.floriophoto.com

Instagram: @jasonflorio | Twitter: @floriophotoNYC

The Gambia - Victims & Resisters Redux, 2021

(L) Pa Ousman Njie, torture victim (R) Banjul street near where he was abducted by National Intelligence agents_2019

Having worked and lived on and off in The Gambia since 1998, Helen Jones-Florio, my wife and collaborator were personally aware of former President Yahya Jammeh’s control over society through fear, intimidation and human rights violations. Jammeh ruled The Gambia as his fiefdom for 22-years, crushing dissent and opposition with brutality. His hit-squad and Intelligence Agency carried out tortures, assassinations, and acts of sexual violence with impunity - journalists were gunned down and disappeared, students shot in cold blood, and even his cousins were murdered on his order. But, society was muted- Jammeh had informers everywhere, and we, along with most residents, dared not criticise or question openly out of fear for our safety and that of our colleagues.

It was not until Jammeh fled into exile in January 2017, after an astonishing election defeat, did the litany of violations under his regime start to come to light. The Gambia has been our second home and we felt it was our duty as documentarians to give face and voice to the victims, survivors, and their families. Despite hundreds of testimonies by both victims and perpetrators at the on-going Truth Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, many Jammeh loyalists are still in denial of the crimes, he and his cadre are now being accused of. Making it important to keep bringing the victims stories to public attention.

Since 2017, we have photographed over one-hundred-and-twenty portraits, sites of violations and recorded video testimonies. Our work aims to expose the wide-reaching forms and scale of abuse - to create a historical archive and to be used as a tool for advocacy and public awareness. Early in the project, we came to understand that many people who sat for the portraits found it cathartic, having previously not been able to openly tell their stories, and so our work took on additional and profound meaning and made it a collaborative process. Alagie Sonko, falsely imprisoned by the regime, said to us “I don’t care what you do with my picture or my story, but the fact you came and listened to me, that is enough”.

Pippa Hetherington

Born in 1971 in Kokstad, South Africa. Lives Cape Town, South Africa

www.pippahetherington.co.za

Instagram: @pippa_hetherington

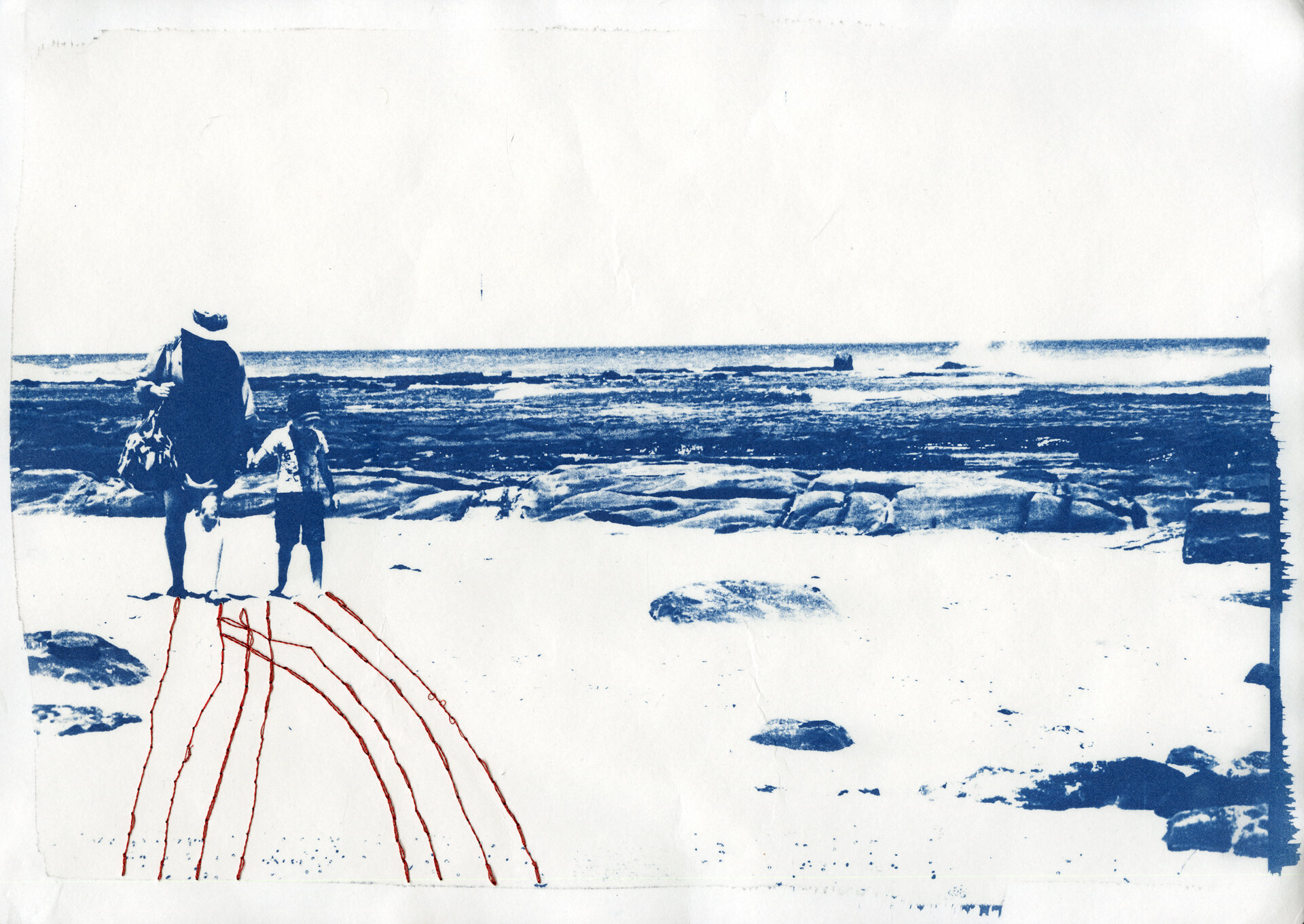

Blueprint Mother, 2020

Untitled

Nearing middle-age, I set off to NYC to study, leaving behind my husband and 21-year-old son. I commandeered my way through 18 months of MFA work. The overnight adjustment was disorientating. I was living on my own, an unfamiliar experience. My identity as a mother was put on practical hold. I found a new tribe of companions and consciously gave myself permission to create work from a deep connection to who I was right there right then. A double-edged sword of being homesick against the backdrop of freedom of space and expression. In the physical space of the city, I was not someone’s mother. Strangely this strengthened my bond with my son in a surprising way. I found a voice in a form of expression that I never thought was valid. And that validity judgement, I realized, had come from only me for all my adult years. What kind of mother had I been? What kind of mother was I to cut the cord by vanishing from our family home? This time I was the one flying the nest.

This brought me into acute appreciation of the competitiveness of motherhood. So often the analysis is sternly against ourselves, never standing up to our high set of unrealistic standards. So often we strive to ‘succeed’ as mothers set against our own constructed framework.

Fast forward to the onset of lockdown in March 2020: after living in separate parts of the world on and off for over five years, my son and I were thrown into the same domestic space. Reconnecting was staggeringly seamless and better than it had ever been. We entered into the space as two individuals who are bonded through blood yet equally have a sense of adventure and ambition. Watching this exceptional human move around the house, tall and long limbed, filled me with ease and comfort. I closed the door on the anxious and strict inner mother-judge and welcomed my new connection to Motherhood into the house.

These cyanotypes were made during lockdown using archival images.

Brian Hodges

Born in 1962 in Santa Monica, United States. Lives in Brooklet, Australia

www.brianhodgesphoto.com

Instagram: @brian_hodges

Odilo Lawiny, 2019

Untitled

Miles from the main roads in rural Uganda, soccer balls bounce unevenly. Playing fields are arid, lush, weedy, sandy—any flattish space will do. Goalposts might be made of rocks or branches. Some feet are bare, others shod in fraying sneakers, boots, or rubber sandals. Yet children kick and chase handmade, lopsided balls with skill and abandon, competing for pride and joy—for the sheer pleasure of playing.

On fields throughout Uganda, rubbish is transformed into handmade soccer balls (Odilo lawiny - as they are called in Acholi language). Odilo lawiny are spun into being with whatever’s at hand: rag or sock, tire or bark, plastic bag or banana leaves. Made entirely of recuperated materials, the balls give another life to something that would otherwise just be thrown away. They might last days or months on a field of gravel or hard earth.

These precious jewels are a symbol of Africa’s passion for football. Each is a unique work of art. They speak of the ingenuity and craftsmanship of a continent. They speak of people who manage to do so much with so little.

Zainab Imad Eldin

Born in 1996 in Nairobi, Kenya. Lives in Ruwais, United Arab Emirates

Instagram: @zaionfire

Colored Black, 2020

R1

Colored Black investigates internal racism amongst Sudanese people, more commonly termed colorism, through the lens of a Sudanese, Muslim woman.

In Sudan a spectrum of words is used to describe each shade of skin color, commonly used in a racial context. The primary ones being ‘ahmar’(red), ‘asfar’ (yellow), ‘asmar/bunni’(brown), ‘akhdar’(green), and ‘azrag’ (blue), and over time, the spectrum expanded to include names of particular shades of a skin color. While they are referred to when describing someone, they are also used in a derogatory manner.

It’s a much more difficult struggle for women, having to deal with social pressure on looking a certain way. As a result, many find themselves using harmful chemicals to satisfy these impossible standards; erasing their color, and subjecting themselves to potential harm.

The color blue is particularly notorious because it’s used to describe South Sudanese. Blue refers to blue-black, the darkest shade before black.

The idea of this work is to begin unlearning subtle micro-aggressions that have become ingrained within me. I chose the four primary colors on the scale, and took them by face value, to question the existing scale, and highlight the absurdity of discrimination. The photographs show the portrait, and the color, in a frozen moment of its process of deterioration. This slow process of ink dripping alludes to the lifelong process of actively unlearning racism. The photographs are arranged in order from the lightest to the darkest shade, each color in its own row.

I used a projector to project each color on me against a white wall, and made the photographs. Using an inkjet printer, I printed them on clear acetate, scanned them as soon as they came out of the printer and then hung them on a wall. Every 20–30 minutes I would take them back in and scan them, and hang them again. The waiting time varies with each ink color, so I would sometimes scan every 5–10 minutes, and sometimes I would wait 40 minutes or even more than a few hours. The final outcome is a print of the scan.

Matt Kay

Born in 1985 in Witbank, South Africa. Lives in Capetown, South Africa

Instagram: @mattkayphotography

Maiden Flight, 2020

Untitled

Most hives only have two small openings, like eyes. Each bee walks out through a tunnel of light and returns flying into the dark.

When I met Mark he had returned to his family home after the death of his Mother. The property was once a famous garden, famous for roses. We talk through glimpses of his life, He fought in Angola, he was married, he has lost a son. Mark names his hives after the children from the properties where he caught the swarm.

Our lives intersect through my father, born in the same year, 1955 both belonging to a system that has been rejected and share a growing understanding that they are damaged from their past. I have never seen my father as gentle as when he’s working with wounded and orphaned birds, I’ve never seen Mark more present than when he’s tending his hives. Safety comes in the form of solitude, a push back against the interconnectedness of a technologically progressive world, a slow but deliberate attempt to regain tenderness.

The small outside cottage where we meet to take these photographs has a hive between its wooden walls. If you press your head against them you can feel and hear the swarm vibrating. He has named the Queen the Empress and can tell you where the workers are coming from by the colour and smell of the pollen.

I often think on the idea of the hive, of belonging and the swarm, the human-irony of only being able to participate in its community by protecting yourself from it.

The ritual actions of lighting a smoker and donning a suit as necessary forms of separation and solitude.

Beautiful in its absurdity.

Gatekeepers, guardians and Queens, orphan cranes and disguised priests.

Honey, smoke and feathers.

Adil Kourkouni

Born in 1990 in Marrakech, Morocco. Lives in Marrakech, Morocco

Instagram: @adilkourkounistudio

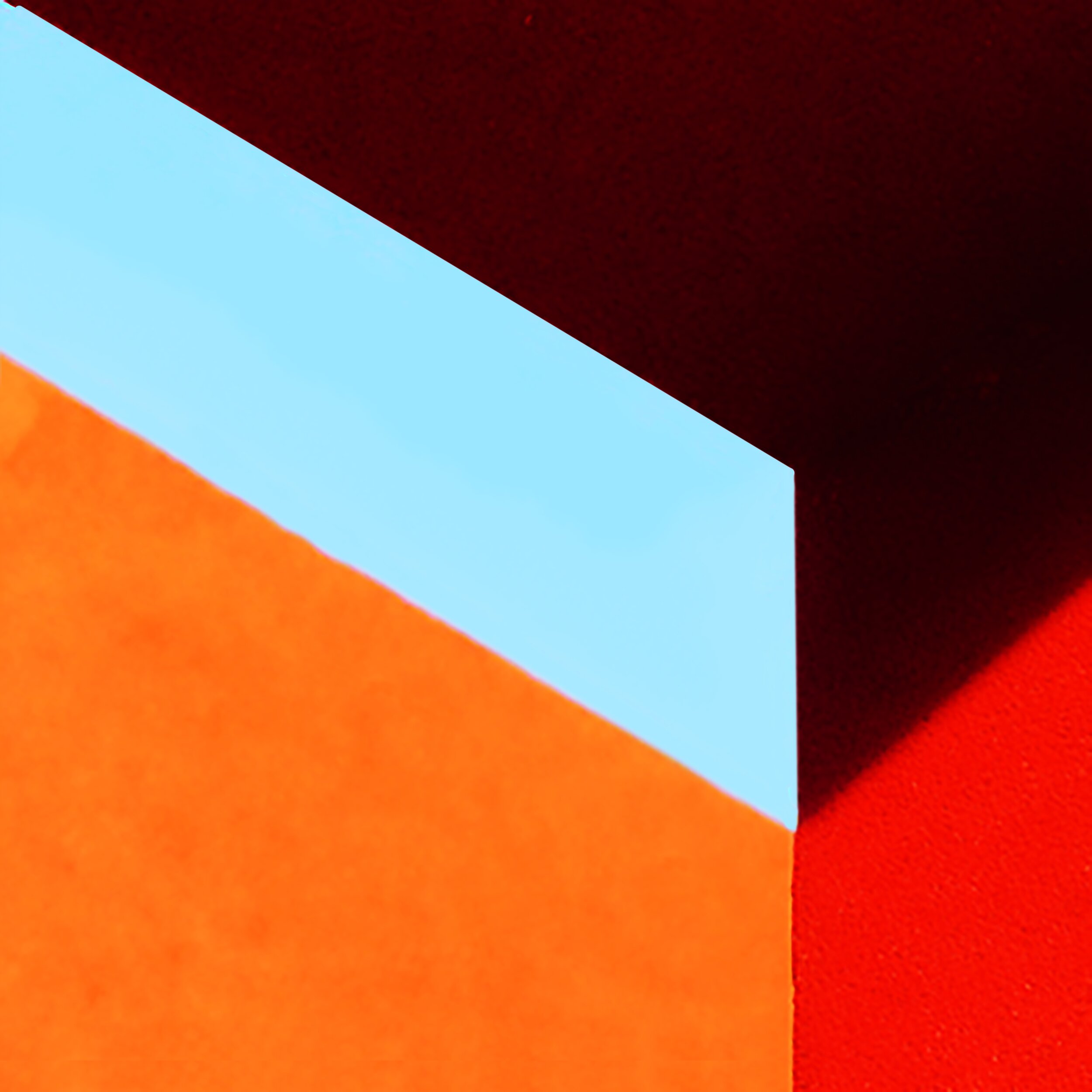

Utopic Perception, 2017

Untitled

"Utopia is what we lack"- Edouard Glissant.

It all starts in Marrakech by observing and spotting urban constructions during walks and daily journeys at different times of the day. Then, back on the spot, I frame and photograph the balance between the sky and the ochre walls of the city, which are usually ignored. These "stops on details" are a step back, a necessary breath to appreciate the hidden beauty of this coexistence.

These photographs of cropped fragments become minimal graphic compositions, geometric abstractions that evoke the world of Esther Stewart and Frederick Hammersley.

My photographs reveal utopian plots whose contemplation transports us beyond the original anguish provoked by the cold repetition of urban geometry.

In terms of procedure, these were just photos taken with a Nikon camera and a 35-18mm lens with some modifications to (cropping; hue and saturation; vibrance; colour balance).

Tamary Kudita

Born in 1994 in Harare Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. Lives in Harare, Zimbabwe

Instagram: @africatotheworldzw

African Victoria, 2020

The Gathering

My work attempts to convey a truthful narrative and demonstrate how I engage with issues of invisibility, re-contextualization, appropriation and subversion to preconceived ideas of black personhood. I look at how our unchosen histories have shaped our contemporary state. Furthermore, my work speaks directly to the common reality amongst people of colour of an ‘obscured history’ which often negates our individual stories. Thus, making a commentary on history and its selective unfolding. Through portraiture, I merge my contemporary aesthetic with a historical aesthetic as a way of showing how the old informs the new.

Stemming from my ancestral mixed race lineage, my images take on superimposed characters. I intentionally use African elements that have been superimposed filtering through a western medium. This layered symbolism illustrates an affiliation with a multifaceted identity. Both innate and superimposed variations of my work are capable of division into those which are more and those which are less obvious to the human eye. My work carries layers of signification and meaning, illuminating once invisible bodies by making them hyper visible while undermining the authority of simplistic readings of the black body.

Furthermore, I explore the place of African fabric in the refashioning of cultural, racial and gendered identities as well it’s use as a vehicle with which to challenge structures of power that render certain people’s histories and cultural expressions invisible. My subjects wear African dresses that have been partially transformed into Victorian regal attire. By reconfiguring the ‘African dresses as Victorian gowns’, I invert the social power indexed by Victorian dress and use clothing in ways that unpick inherited binaries haunting understandings of difference in Post-Colonial Africa. My work gestures towards ways in which I embark on a cultural remaking of the self and other, contributing to new imaginings of African identities. The (dis)-connections between personal history and received social history are an ongoing interest.

DeLovie Kwagala

Born in 1994 in Mulago, Uganda. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

Instagram: @deloviephotography | Twitter: @deloviephotos

Surviving Bery, 2020

“Do you ever feel like you’re suffocating under layers and layers of debris and your body feels numbed by the minute, feeling every inch of you being overpowered and your whole system slowly shutting down in a never-ending loop with sharp daggers constantly poking at your soul? That’s how I have felt every day for the last 12 years of my life. I have a lot of hatred for that man and those that share his skin. I was 7 when I was taken to his house. The world will never know how many times I tried to end my life… to end it all so I don’t have to ever remember what he did to me. Education cost me my innocence and my life altogether. Because if it wasn’t about schooling, then I won’t have ended up at that house.” Farida*, 19, fails to contain her tears each time she narrates her story to me amidst reminding herself that she needs to do this in hopes of saving other girls by reminding them to speak up. 2020

Bernhard ‘Bery’ Glaser, was a German national who illegally operated ‘Bery’s Place’ in Kalangala, on Bugala island in Lake Victoria, Uganda for more than 10 years despite persistent rumors of abuse. Glaser was first arrested in December 2013 on charges relating to child abuse, but he was acquitted due to lack of evidence. Despite this initial arrest he continued to operate a home for girls and young women, where he was responsible for their care and welfare. He was arrested again in February 2019, this time facing 19 counts of aggravated defilement, child trafficking and operation of an illegal children’s home, and it was during this second trial that he died of cancer in May 2020.

He maintained his innocence throughout the court proceedings, despite a litany of evidence against him, and many people observed that throughout his life and trial he seemed to have been granted indulgences that a similarly accused local defendant would not have dreamed of. Survivors have testified that they were groomed by him and were abused throughout their time in his care, while being threatened with homelessness and public humiliation if they spoke to anybody about their plight. In spite of a growing chorus of concern about the actions of his organization, the surrounding community hailed him as a hero for his work. Rumors fell on deaf ears as community leaders closed ranks to protect him.

I spent time with around fifteen of his victims as they pursued legal action against him. From a shelter run by children’s rights advocate Namusoke Asia Mbajja, these strong young women pursued justice despite attacks from the Ugandan media which vilified them, questioned their integrity and painted Glaser as a victim rather than a pedophile. While there is no suggestion of any intervention in the legal processes of either of his trials, justice does not seem to have been swiftly pursued on behalf of his victims, and both the press and the state often instinctively believe Glaser over his victims.

Dillon Marsh

Born in 1981 in Cape Town, South Africa. Lives Cape Town, South Africa

www.dillonmarsh.com

Instagram: @dillonmarsh

Diamond Coast, 2021

(L) Mire, Alexander Bay, 2020. (R) Meander, Oranjemund, 2013

Diamond Coast is a book in the making, and this series of paired images represents a selection of the book's content.

The Diamond Coast is an arid windswept coastline that harbours wealth, but a dwindling supply of it. For millions of years, rivers have slowly cut away at the South African interior, carving shifting paths and reducing rock to sediment. Diamonds were among the spoils, with the purest and hardiest reaching the western coastline unscathed. Here they lay undisturbed until 1925, and over the decades that followed, vast tracks of land were stripped and sifted, fences strung, and entry prohibited. Now diamond yields are declining and many of the mines have closed, leaving land rehabilitation obligations unfulfilled.

It is easy to pass the Diamond Coast and fail to ever see it. The main road connecting Cape Town to Windhoek runs parallel, an hour’s drive to the east, and many of the interlinking roads remain untarred. The small towns that once serviced the mines have dismantled their checkpoints and opened to the public. Many of the original residents have left to find work elsewhere, while others remained to scavenge what was left behind. Newcomers have also begun to arrive, seeking refuge from overwhelming city life. They bring with them optimism and ambitious plans, but the harsh elements are unrelenting, and infrastructure is suffering without the financial support of large-scale mining operations.

I am also an outsider, a reticent visitor drawn to the promise of temporary escape and isolation. I have made repeated visits ever since this region started opening up, and over time I’ve inadvertently become a witness to the changes taking place here. It is unclear what will happen next. Maybe these struggling towns will find a new lease of life, or maybe they will suffer the same fate as so many other mining towns and simply fade away. In the meantime entropy holds sway here on the Diamond Coast.

Fabrice Monteiro

Born in 1972 in Namur, Belgium. Lives in Ngaparou, Senegal

www.fabricemonteiro.viewbook.com

Portrait-Type, 2020

Homme Type Fon

During an artistic residency in Benin with the Fondation Zinsou, I decided to revisit the photographic technique of the "composite portrait" developed around 1878 by Francis Galton. This technique was first used to define the typical portrait of the criminal. Later, Arthur Batut (1846-1918) proposed to use the same technique to create the typical portrait of a family, an ethnic group or a race. The process consists of a millimetric superimposition of exposed portraits of individuals belonging to the same group. The result is supposed to give a representative portrait of the group, leaving only the main features characteristic of the group visible in the image.

The "Age of Enlightenment" saw the birth of racialism in Europe, which served as a tool to classify and divide people. The aim of this work is to demonstrate that the notion of race being totally subjective, the use of photography to identify it was very disappointing. "By trying to prove too much, you prove nothing except that all men are brothers.

I travelled around Benin to meet eight ethnic groups: the Peuls in Tanguieta, the Somba in Koussou, the Yoms in Sapaha, the Dendi in Songo, the Baribas in Boko, the Tofin in Sohava, the Nago in Pobé and the Fons in Lokozon. Each portrait is composed of 6 superimposed portraits of individuals belonging to the same ethnic group. "La femme Type Fon" is the result of six superimposed photographs of women. The final portrait looks like none of them and all of them at the same time. From a distance you can see one face and when you get closer you can read the superimposition of the faces. I followed the operating process of ethnographic photography with a backdrop installed on a removable frame, a height-adjustable stool and a holding system at the back of the head to keep the subjects upright, the eyes being the central reference.

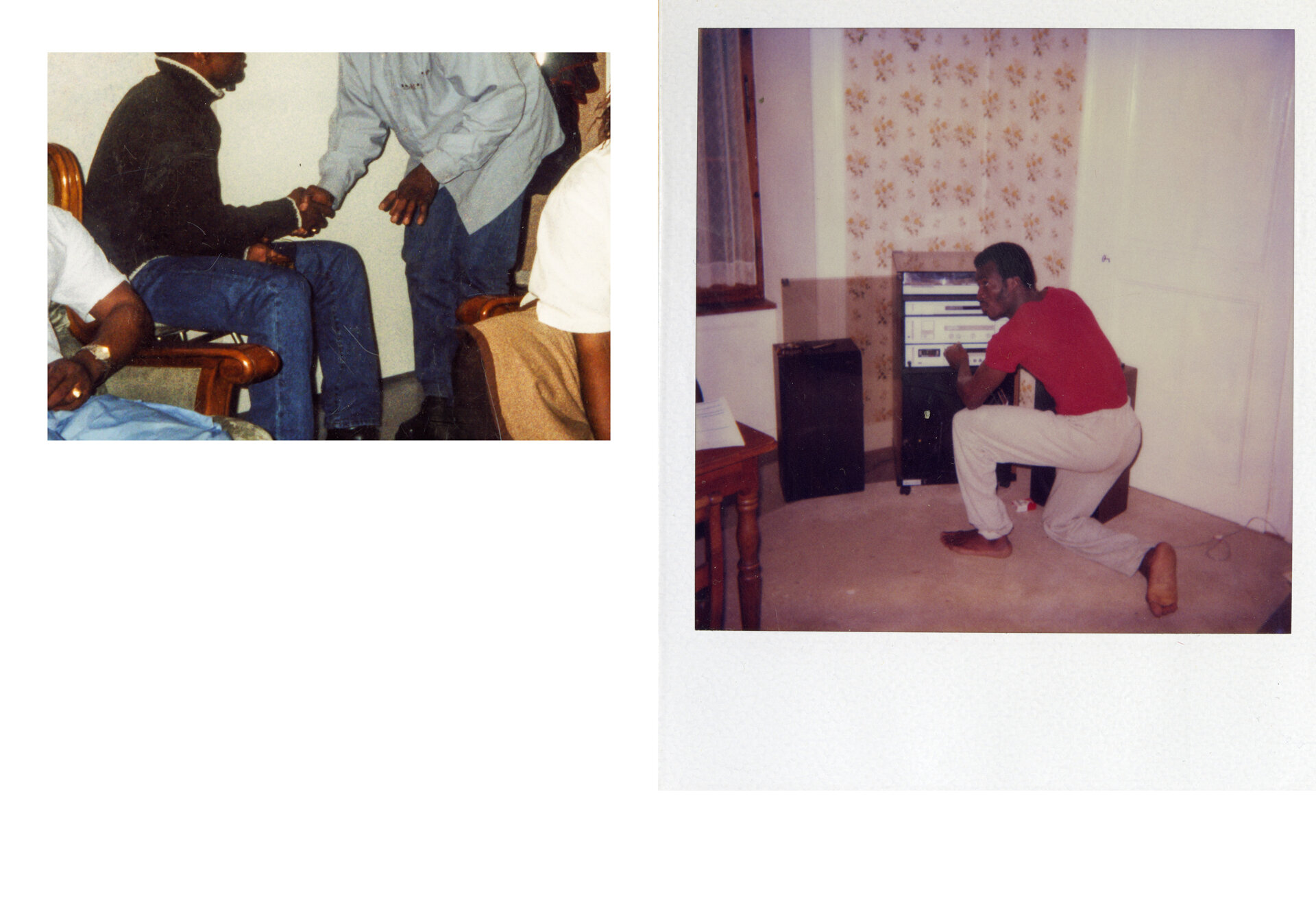

Claudia Ndebele

Born in 1989 in Montreux, Switzerland. Lives in Vevey, Switzerland

www.claudiandebele.ch

Biso Bana Ya Poto – Nous les Enfants Congolais d'Europe, 2020

Untitled

Biso Bana Ya Poto is an expression in lingala, one of the four languages in the Democratic Republic of Congo, that means “we, the Congolese children of Europe”. Being used to describe and define the descendants of the Congolese Diaspora, it represents the starting point of this personal project around questions related to “Personal Identity” and “Native Culture”.

From the youngest age, we are defining our identity and our marks based on our geographical location, where we live. Automatically, we are adapting our traditions and behaviors to the ones of our social surrounding. Activities, hobbies, birthday parties, school and friends are many of the different situations that will shape our identity.

Fear of being rejected or different from others are also additional factors to be considered. These last aspects could be emphasized by misrepresentation of some minorities in every type of media, books, movies, cartoons, etc. These elements prove how vulnerable and easily influenced we can be towards shaping our identity as childrens. Therefore, growing up with two different cultures can often lead into forgetting or pushing aside one of them.

This selection of photos has been chosen amongst the 122 archive pictures held in this 209 pages editorial project.

The story of this project is cadenced through personal and interviewees’ photos, as well as individual experiences, difficulties and feelings that we, the Congolese childrens living in Europe, might encounter. On top of celebrating the story of Congolese Diaspora’s descendants in Switzerland, this work has as a main objective to describe - and witness - that strange border when two different cultures are being mixed up. This project offers an immersive experience to anyone thinking and questioning topics like Personal Identity or the Diaspora.

Emeke Obanor

Born in 1972 in Agbor, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.emekeobanor.com

Twitter: @emekeobanor | Instagram: @emekeobanor

Tree of Freedom, 2020

Untitled

The Boko Haram sect, a terror group in Nigeria, are notorious for kidnapping of ladies, both young and old. Several global agitations for the release of the kidnapped girls have come and gone. For instance, the themes “Bring back our girls” and “Release Leah” connected to the Chibok and Dapchi kidnappings, respectively, were all over the media at different times. Whereas some of these girls have been released, many others are still in captivity till today. The voices of solidarity have moved on to other issues, and it appears the girls have been forgotten. However, there are still a few who are chanting for their release. "Tree of Freedom" is a portrait series of young Nigerian activists uniting to raise awareness for the freedom of the girls still left in the captivity of Boko Haram. Each of the portraits showed seeds and tree saplings which in African mythology symbolizes life, strength and resilience. In some traditions, trees are planted to represent an individual who may be under any form of bondage, like ailment, captivity or oppression, and it is believed that as long as the trees are nourished and watered to grow, the individual concern would also be sustained. So the seed and tree saplings were symbolic of this tradition undertaking for the sustenance of the girls in captivity.

The activists also wrote letters and poems to the victims to serve as prayers and consolations to the victims. These write-ups were addressed to the victims, and the tones are of hope and courage in the face of terror. They believe that somehow, the notes are means of prayers, and fate would keep the captives long enough to read them.

Those abducted may be forgotten by many, but not by these young activists, so would you plant a tree today for the release of the captives: A Tree of Freedom.

Joseph Obanubi

Born in 1994 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.josephobanubi.com

Instagram: @josephobanubi | Twitter: @josephobanubi

Techno Heads, 2020

Seagull dance II

Techno-Heads examines globalization as it affects technology, continued human interactions as well as movement - Navigation of spaces. The project focuses on how individuals within contemporary African society navigate through day-to-day patterns of life, infiltrated with technology, even in its simplest form. It shows how the contemporary society strongly revolves around and depends on technology for communication, motion, and navigation, all of which are central aspects of human existence. This project portrays figments of this phenomenon as part of a being, swapping naturally occurring forms of the subjects with an infusion of mechanized forms projecting the idea of a techno-utopia. It also dabbles into the concept of Metaphysics in the African context, exploring how identity, space and time have become intricately linked with even the simplest products of technology. It seeks to merge African metaphysics and (simple) technology to explain alternate reality and how they portray techniques and concepts of freedom for Africans in contemporary society.

Léonard Pongo

Born in 1988 in Liege, Belgium. Lives in Brussels, Belgium

www.lpongo.com

Instagram: @leonardpongo

Primordial Earth, 2021

Untitled

By exploring the diversity of landscapes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, artist Léonard Pongo offers an allegorical imagery of the country. Imbued with a sense of magical beauty and mystical power, the landscape seen through his eyes becomes a setting to rebuild the self, and the earth becomes the source of an awareness from which tradition, philosophy and conceptions of the universe emerge. For Léonard Pongo, exploring the environment, as well as sensory experience, are pathways to an emerging vision of the world – it is by becoming one with the landscape that it becomes possible to engage with life.

Drawing inspiration from Congolese traditions and Kasaian cultures, “Primordial Earth: Inhabiting the Landscape” presents the landscape as a character with its own will and power, like an open book that tells the story of humanity and the planet, with Congo at its centre. The resulting installations combine traditional photographic prints with textiles and video works into a multidimensional allegory based on three central themes: creation/genesis, the apocalypse and the eternal return.

This project questions man's relationship to place and territory at a symbolic and sensory level, while offering a reading of life, humanity, and the planet, from a contemporary Congolese point of view.

Mahefa Dimbiniaina Randrianarivelo

Born in 1991 in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Lives in Antananarivo, Madagascar

www.artofmatchboxd.com

Instagram: @artofmatchboxd

Vices & Virtue, 2019

The Ballad of Mona Lisa

Originally, the seven capital vices are classifications of vices within Christian teachings. They are pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth, which are contrary to the seven heavenly virtues.

Although this concept is inspired by Christian culture, I just wanted to show that we are all equals. We all have our flaws, our good sides, our sins, and that's what makes us unique, that's who we are. We're all trying our best in this world wherever we are, whatever we believe, and I think that is beautiful. All my works revolve around self-appreciation and equality between all of us. I think we should do good around us, but before that, we have to accept ourselves. For me, photography is just a medium, it is the most efficient way I found to express myself. I mainly do surrealist portraits because I want the viewer to be able to identify himself and make his own opinion about what he sees.

This series contains 14 images, two for each sin. Technically, the two main characters are in the same world, the same background, always to convey the feeling of equality. With the help of photo manipulation, I created surrealist portraits to represent each sin. All images were done in studio. I use many symbols and I am really inspired by artists from different eras and different styles: Frida Khalo, Banksy, René Magritte, Jeff Koons, Green Day, Wes Anderson etc but I always try to make my concepts as open as possible for anyone to feel.

Paul Shiakallis

Born in 1982 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

www.paulshiakallis.com

Instagram: paulshiakallis | Twitter: @paulkallis

Hotel Hillbro, 2020

“When you make sex, I know you can catch herpes if the skin breaks. Anyways, what can you do? They have it, I have it. I can’t stop. When the balls are heavy, you go.” 2019

Hillbrow is an inner-city suburb of Johannesburg. It was a whites-only area during apartheid. Black Africans, although only a rare few, managed to co-inhabit while the police turned a blind eye. From the 1970s, Hillbrow, at the heart of Johannesburg’s disco life, was considered the most cosmopolitan real-estate in South Africa. Towards the end of apartheid, many migrants from Southern Africa moved into Hillbrow as their first point of contact to Johannesburg. This migration led to the European residents of Hillbrow fleeing to the safer suburbs of Johannesburg. Hillbrow subsequently plummeted into poverty, with its overpopulation and lack of investment. Crime statistics tarnished its name and deemed it a no-go zone; Hillbrow became Johannesburg’s most dangerous suburb.

“To mention Hillbrow is to evoke a wide range of reactions: to some it is the embodiment of sin, violence and evil, while others view it as a hub, radiating excitement and all the colour and glamour of a plastic age. Yet others regard Hillbrow as a place to be totally alone and anonymous…” – Excerpt from the book ‘Hillbrow’ 1984.

Hotel Hillbrow is about my ventures into the bars, the clubs and the hotels of the Hillbrow nightlife, and my interactions with the people that frequent these spaces. Through casual conversations, I explore themes of access; sex, love and companionship, God and illegal activity, free choice versus cultural pressures, the search for recognition and the will to succeed.

The air is a brew of smoke, sweat and piss. Art deco desperately clings to the walls. A pastor-by-day bouncer-by-night greets friends at the door with a “long time no see”. I enter with preferential treatment. Congested hallways lead through a gauntlet of sneaky hands and suspicious eyes. The one-armed pool player conquers the table — a woman in seductive blue sips from a neon straw. My arrival is welcomed by two friends at the bar sharing a whiskey and Redbull, I am happy to see them. I leave my world of formalities, safety and comfort to enter theirs.

This series is a rare account of these spaces as cameras are generally forbidden.

Mauro Vombe

Born in 1988 in Maputo, Mozambique. Lives in Maputo, Mozambique

Instagram: @maurovombe

Faces, 2018

Untitled

Faces is a series which seeks to explore ideas of identity and interconnectedness – that we are all individual parts of the same organism. The groups I photographed are of different religious and cultural backgrounds, genders and age groups yet across them there are moments of similarity. The anxieties and joys on one face may find itself echoed on the face of another.

Similarly I am interested in the face being the first mode of expression – the first word. Our faces are how we present ourselves and navigate the world. The faces in these images are rendered in sharp focus and they are individual in their identities, yet they also naturally and seamlessly assimilate into the larger group.

In this moment of global uncertainty, I am interested in ways of being together when we cannot be physically close to one another.