CAP Prize 2019 | Short List

CAP Prize 2019 | Short List

The following 25 artists – in alphabetical order – were selected by the CAP Prize panel of judges comprising 19 international curators, editors, publishers, and artists, from hundreds of applications for the CAP Prize 2019. Five of the shortlisted artists will be awarded with the CAP Prize 2019 for Contemporary African Photography to be announced at photo basel in June 2019.

ROGER ANIS | ZINYANGE AUNTONY | SIBUSISO BHEKA | JODI BIEBER | MARGARET COURTNEY-CLARKE | SANNE DE WILDE & BENEDICTE KURZEN | SAIDOU DICKO | MEDINA DUGGER | ANDREW ESIEBO | THEMBINKOSI HLATSHWAYO | OSBORNE MACHARIA | TSOKU MAELA | ALICE MANN | XOLISWA NGWENYA | FREDERIC NOY | JOSEPH OBANUBI | BRIAN OTIENO | SAMANTHA REINDERS | RIJASOLO | FATOUMATA SAKHO | ABDO SHANAN | MOLEBOGENG THOKA | JANSEN VAN STADEN | JOHN WESSELS | ETINOSA YVONNE

The call to the 9th CAP Prize will open 7 November 2019.

Roger Anis

Born in 1986 in Egypt. Lives in Cairo, Egypt

www.rogeranis.photo | instagram | twitter

Shaabi Beaches, 2017–2018

‘Shaabi’ Beaches The word ‘Shaabi’ in Arabic cannot be translated into one word in English. It is a reference to social class, standards, popularity, behavior, culture, and traditional communities. While economic strain hits many in the country financially, Egyptians always find a way of spending at least one day of summer on the beach. it's also not the economic crisis but making a lot of beaches in Egypt private and costs a lot of money to go to. Many travel for hours away from their cities and villages in buses, trains, and all kinds of transportation just to get a feel of the sand on their feet and salty water on their bodies. but for those who can't even afford this they find other alternatives, like a swimming pool in a slum or waterfalls in a city south of cairo. This photo essay unveils a layer in Egyptian society through portraiture of families & People on these beaches and other spots where they can enjoy swimming and the water touches their body.

Zinyange Auntony

Born in 1984 in Zvishavane, Zimbabwe. Lives in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe

www.zinyange.com | instagram

Power and glory, 2017–2018

Power and Glory is project that provides a historic visual documentation of the violence experienced by ordinary Zimbabweans at the hands of the state security forces and party agents. From the defining moment in Zimbabwe's history to capturing testimonies of survivors of the Gukurahundi killings in the 1980s which saw the massacre of an estimated 20,000 people and the current political tensions over the legitimacy of the ruling ZANU-PF party, this project chronicles the stories of the impact of state power and internal power struggles on citizens. Nearly four decades on since the liberation war, the glory stories still occupy the central narrative in Zimbabwe's political discourse as the liberators who brought the country freedom, fight to retain control amongst themselves, against perceived dissidents and political opposition movements calling for greater democracy in Zimbabwe. Using a documentary approach to give voices to the many suppressed stories of violence and survival, this series, which has been ongoing for three years now, aims to show how power changes form and shape but it is the same force, the quest for glory, which pushes the ruling elite to maintain authority at all cost. Often the boundaries between the judiciary and the executive are blurred and justice is an elusive ideal for those who have suffered. In short, Power and Glory hopes to give a better visual understanding of post-colonial Zimbabwe's cyclical history and the oppressed voices living beneath the throne. A visible trail of evidence that the state-orchestrates campaign of killings, torture and abductions continues four decades after independence go on as ZNAU PF fights to hold on to power.

Stop Nonsense is a night documentary project in which I seek to document the changes induced by the wall built around my grandmother’s house. The vocable “Stop Nonsense” which is generally used in South African townships refers to any wall constructed with bricks and cement with the intention of providing protection and avoiding conflicts between neighbors. The project site in a small township called Phola Park located in Thokoza, east of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was established in the early 1950’s under the racial segregation government act Native Urban Area Consolidation Act. The Township is a place with distinct ethnic groups but is predominated by low-class Xhosa people. I started this project in late 2015 when the wall was built up, I was spellbound by the sudden change after the wall had been constructed. Things were not the same anymore, particularly at night. The yard had a different ambiance, beyond the borders of the wall existed a vibrant township during the night. In this body of work, I have been capturing what is happening, but I have also been trying to recreate artfully pictorial scenes of the events prior to the construction of the wall as well as the events leading to its creation.

Jodi Bieber

Born in 1966 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives Johannesburg, South Africa

www.jodibieber.com | instagram | twitter

#i, 2016–2017

Design: Brenton Maart

#i focuses on the youth of Johannesburg, aged 15 to 23: a generation that did not grow up under apartheid, and who have the ability to access and communicate using technologies that integrate them within a larger global community. Having different historical experiences than those of their parents, they have their own visions and expectations of themselves and of South Africa. I collaborated over a period of three years, starting in 2016, with a wide range of 45 young people from Johannesburg – from different cultures, income groups and areas – to produce a portraiture project that expresses young people’s visions of themselves and their country. These visions are expressed in the words of the young people, their own photographs from their phones, and the portraits I photographed of each individual. I have taken on this project because I believe that young people can lead our future with new, fresh narratives. The older generation’s lived experience is during apartheid in South Africa and – through extensive interviews with the young people on this project – the words echoed were for fresh new conversations, new ways of being, of living their lives and creating their own stories. With the forthcoming national election in South Africa in 2019, this exhibition is a portrait of a generation that will play leading roles in a pivotal moment in South African history. Another aspect to the project is that it is collaborative on many levels. I connected a participant to an editor at Caxton Newspapers for an internship. In exchange for looking for participants, I gave a talk and slideshow at Rosebank College in Braamfontein to journalism and media study students regarding my career and projects. Participants have been informed of developments throughout the three years via WhatsApp. They have received an artist proof print of their artwork. I worked with the designer Brenton Maart, to combine all the creative elements together to communicate as a whole. For us as a nation in any part of the world to move forward we need to embrace new ways of being and seeing the world.

Margaret Courtney-Clarke

Born in 1949 in Swakopmund, Namibia. Lives Swakopmund, Namibia

www.margaret-courtney-clarke.com

Cry sadness into the coming rain, 2016–2019

Namibia is steeped in histories dating from the earliest inhabitants – San, Herero, Namaqua, Damara et al to German occupation, to South Africans and apartheid, and now to ‘liberation’ and statehood – a nation of diverse peoples and cultures in a land of seeming nothingness and unparalleled light. I seek out the traces of their passing on the land.

‘Cry Sadness into the Coming Rain’ is a record of this social process.

I explore the volatile and unstable space around me and the contradictions in the landscape where cultures and identity are at odds with neocolonialism.

The existential world of the people I photograph is located in an unforgiving environment where life is precarious: little or no rain, scarce water and food, people abandoned by their government and forced to migrate to flee the emptiness... In their rootlessness the only anchor is the expectation that life will persist against these odds.

I keep returning to the women I have met, photographing them anew as they share their unfolding stories. My art derives from this space, the point where freedom meets responsibility, rationality meets imagination, and self meets other. This silent point is the source of all that is humanly significant.

As a woman, born of this place, I seek to build relationships over time, to expose viewers to familiar places and ask them to question their perception of those places within the “New Namibia,” a country that is being sold off to mining magnets and unsustainable tourism.

Almost thirty years since independence, the struggle for many Namibians is to subsist and often to merely exist, on the very land they fought for. One quarter of the population lives a basic life in informal settlements; inside rudimentary shelters and in shacks, without the security of ownership, without basic amenities… on patches of desolate and overgrazed land where survival depends on a drop of rain that might fall. After a life of travel, I have turned my lens on the aspirations of the poor, their quest for shelter and water in a ravaged land, and on the environment in crisis.

Sanne de Wilde & Bénédicte Kurzen

Born in 1987 in Antwerpen, Belgium. Lives in Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Born in 1980 in Lyon, France. Lives in lagos, Nigeria

www.noorimages.com

Land of Ibeji, 2018

‘Land of Ibeji’ is a collaborative photographic project discovering the mythology of twinhood in Nigeria“Ibeji” meaning 'double birth' and ‘the inseparable two’ in Yoruba stands for the ultimate harmony between two people, the rate of twin births in West Africa is about four times higher than in the rest of the world. The centre of this twin zone is Igbo-Ora, a sleepy southwest town in Nigeria.

Communities have developed cultural practices in response to this high twin birth rate that vary from veneration to demonization. In some areas, shrines are built to worship the spirit of the twin and celebrations are held in their honor. In others, twins are vilified and persecuted for their perceived role in bringing bad luck in particular to rural communities. In Yoruba beliefs each human has a spiritual counterpart, an unborn spirit double. In the case of twins the spiritual double has been born on earth. The friction, between communities celebrating twins and rejecting them, lies in perception of the twin as an extremely powerful spirit. Some see it as threat and as something that cannot remain on earth and has to be sent back to the heavens where it normally resides.

Through a visual narrative and an aesthetic language that is meant to reflect and empower the Yoruba culture that celebrates twins, the two photographers extend their gaze beyond appearance - with symmetry and resemblance as tools- to open the eyes to the twin as a mythological figure and a powerful metaphor: for the duality within a human being and the duality we experience in the world that surrounds us.

Benedicte Kurzen and Sanne De Wilde visited three locations, each of which weaves in a new thread to the visual narrative. From an orphanage in Gwagwalada, an area where twin killings still take place, the focus shifts to the other end of the spectrum in Igbo Ora and Calabar, where twins are venerated and celebrated as a symbol of fertility, good luck and abundance. The photographers are using various genres with duality as a key theme: the metaphor and the literal, the visible and the invisible, the material and the spiritual.

Saidou Dicko

Born in 1979 in Deou, Burkina Faso. Lives in Paris, France

instagram

The shadowed people, 2018

WHO ARE THE SHADOWED PEOPLE?

I am the prince who reigns in joy, by sharing and in mutual help, in spite of the obstacles of the daily life. My throne is on an oil field, my people do not have access to it, and my kingdom is on an untapped farmland. I am sure and I hope (Hope) that our children will cultivate all our fields and will share the crops in the night under the trees and the sunlight. I am the queen mother hen who was plucked by my princes and princesses.

Hope (Hope) with all my heart that they will fly with my feathers.

I am the child, happy and funny, surrounded by adults haunted by their glorious past and concerned about their future, while I take advantage of the present, and I hope (Hope) to share their glorious future...

+ With an angel face I am the capricious child With an angel face. My days are punctuated by tears, broken joys and unpaid claims. I hope that when I grow up I will look like my little sister of 2 years old who is funny happy sharing and autonomous...

I am a human being transformed into a shadow by an artist who has had the chance to travel to several countries. He made photos in which he integrates my photos of everyday life or not. He turns my body into shadows in his photo studio which is in perpetual motion. I hope (Hope) that I will also have the chance to travel as much as my shadow.

I am the shadow that navigates a virtual world that has become so real that my reality has become virtual.

We are in a world filled with shadows surrounded by a few people. We hope that the majority of our shadows will become the people we were.

Why did we become spectators of drama that we could have avoided? Why are we so alone in the middle of all?

I'm just a shadow, your shadow, their shadows, my shadow

Medina Dugger

Born in 1983 in Corpus Christi, United States. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.medinadugger.com | instagram | twitter

Enshroud, 2018

Inspired by Muslim women in Lagos, 'Enshroud' reveals the veil primarily in an abstract sense, featuring its forms, patterns, colors and its contribution to identity, self-expression and style. Nigeria is comprised of a roughly half Muslim and half Christian population, rendering the hijab a very visible symbol of faith and custom. Representations of the veil today are incomplete without noting its position as a politically charged symbol. The series also reflects on perceptions and realities surrounding the women who wear veils —garments which have a long and complex history that predates Islam. In ancient times, veils indicated a woman’s social status and religious devotion. Today, the hijab is often reduced to a vilified symbol, rendering it a pawn in the nationalistic culture of fear. Women in hijab risk stereotyping, social exclusion, judgement and abuse. Many associate the veil primarily with extremism, male supremacy and female suppression. These realities do exist, however they do not represent the complete story. Many women who veil feel it is a matter of choice and choose to do so to preserve their modesty and out of respect for their religion and tradition. In the West, the veil has also come to symbolize a position against islamophobia. Nike recently released the Nike Pro Hijab for female Muslim athletes and Kenyan-American model Halima Aden is the first model to appear in hijab on the cover of British Vogue. Veiling in Nigeria is influenced by cultural practices and reflect an affinity for bold colors, textures and patterns. As author Fadwa El Guindi states, “the Western term “veil” is indiscriminate, monolithic and ambiguous, as there are over 200 terms in the Encyclopedia of Islam for dress parts, many which are used for veiling”. With burqa bans and countries banning veils and head coverings in schools, what the world sees as ‘socially acceptable’ in regards to religious and personal expression has yet to be defined. In 'Enshroud', women twirl and jump, their bold brilliant veils assuming colorful, abstract shapes as met in Lagos. The women take on a carefree weightlessness, free from the politically charged anvil of judgement and politicization.

Andrew Esiebo

Born in 1978 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives Ibadan, Nigeria

From second hand in Lome to a second life in Paris, 2018

It is common for western charities to collect used clothes and ship them to Africa as aid. But these goods, discarded by well-intentioned Americans and Europeans, are rarely given to the end-users as charity; instead, the donations are mostly sold to exporters who make huge profits selling second-hand goods in markets all over the continent. While some African countries have banned the importation of second-hand clothes in a bid to protect local clothing and textile industries, in Togo the second-hand clothing industry – worth an estimated US$54 million – is booming. Amah Ayivi is a Togolese designer and stylist living in Paris and the founder of Marché Noir (Black Market), a cult pop-up boutique and fashion brand that encapsulates the afropolitan aesthetic. After painstakingly selecting the items that reflect his personal style from the huge 45-kilogram bales that fill warehouses in and around Hédzranawoé Market, Ayivi takes the second-hand clothes that originally come from Europe and North America as charity and ships them to Paris where he curates and sells them as chic vintage clothing at a considerable profit. Ayivi’s subversive business model repackages western cast-offs as desirable items of value back in the west. Marché Noir also provides the perfect example of the potential of the circular economy to curb the excesses of fast-fashion and empower African entrepreneurs in the Global North.

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo

Born in 1993 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Johannesburg, South Africa

instagram

Slaghuis, 2016

Slaghuis

My room is a mess.

I can’t keep it tidy. I don’t try hard enough.

I am ashamed. I am accountable. I am afraid. I am angry. I want out. I want to get bloody violent.

Is it passed on? Is it intergenerational?

I have a fear of being an adult with a really messed up room. Something is not quite appealing in that.

Growing up in a home with a tavern, I have been confronted with realities that made me want to escape the space. A place of refuge or safe haven should have been my home, but it couldn’t be because it was the extension of the tavern. Perhaps my mind might have been a refuge, but it too was violated. It became a tricky escape. The violence and schizophrenia of a society would be enveloped in this one space. It was ‘my bread and butter’— its’ infamy coined it ‘Slaghuis’.

Loudest in their silence, I confront the unresolved issues I have with the tavern. I confront my violated or perhaps traumatized mind. I confront the memory.

A drunken violence A drunken depression A drunken fear A drunken last A drunken happiness A drunken abuse A drunken love A drunken rape A drunken fuck A drunken anxiety A drunken death

A Societal trauma. The personal is political. The microcosm is the macrocosm. And vice versa.

Osborne Macharia

Born in 1986 in Mombasa, Kenya. Lives Nairobi, Kenya

www.k63.studio | instagram | twitter

Remember the rude boy, 2017–2018

'Remember the Rude Boy’ is a 3 part photography series impelled by the challenges brought about by loss. It begins with a tailor, celebrated amongst his peers for bringing colour to the ghetto. He inspired many to look for hope in the things they owned and had access to. One of them being the thrift market, it was his favourite place. He knew the best vendors and sourced for affordable fabric or second hand clothing that he could transform into masterpieces. He was the father and mentor to my good friend and stylist, Kevo Abbra. He was also an icon to his long time friends in the tailoring industry in the ghetto.

Instead of taking time out to grieve the sudden death of a dear father and friend, shortly after his burial, they set up tribute shows in different hoods in Nairobi, Kenya, to model collections inspired by their mentor. The tribute honouring Kevo Abbra’s father was also taken further to Accra, Ghana, where casual tailors felt inspired to improve on their day-to-day simple designs and strive to become iconic fashion designers.

At the time, I was fortunate enough to be introduced to 4 African-American War Veterans from the State of Michigan who despite all odds, survived war and on a day to day basis continue to survive the impression of war on their memories. Kevo Abbra joined me on this trip and from his interaction with these heroes, they soon discovered they had a common denominator, fashion. And so, they worked together to bring forward their best selves and the 3rd series of ‘Remember the Rude Boy’ was ignited.

Tsoku Maela

Born in 1989 in Lebowakgomo, South Africa. Lives in Lebowakgomo, South Africa

www.tsokumaela.com | instagram | twitter

Aesthetics of freedom, 2017–2018

To enslave a people one need not shackle them in chains, but to capture their minds. Shape them. Mould them.

For centuries a Western narrative was manufactured of Africa that exoticised her cultures for an aesthetic without heritage to benefit the white Westerner and European in the form of asserting cultural dominance and profit. The process in which this narrative was realised and achieved consists of structural and institutional methodologies that served to erase, misrepresent and ultimately condition a new generation of Africans to seek and find solace in Western values instead of their own ancestral beliefs. Through education a continued European prevalence was reinforced by the exclusion of native languages and historical literature on the continent, with tribal figures often depicted as primitive and unknowledgeable, grateful for the education and structural developments that were brought to them by whiteness. Therein lies the folly of white saviour mentality - that in a modern society, any man, woman or child who adorns the fabrics or ornaments of a cultural kind is primitive. The truth is, just like Westerners see genius and hidden messages in DaVinci’s paintings, Africans left their history and ancestral knowledge in the symbolism representative of their cultural heritage.

“Aesthetics of freedom” is a combination of two series of works titled “BE GLAD U R FREE” (2017) and “Appropriate” (2018) in a bid to create a discourse on a colonial mentality created by an oppressive and biased structural system and its prevalence in a post-colonial world during the era of globalisation. The former series takes a look at the concept of freedom in a contemporary neoliberal world by humanising often politicised issues and interrogating the power of choice. The latter takes a look into the value of African culture at its intersection with commerce. Together the works not only highlight but presents the symbols and aesthetics representative of Africa’s wealth that has been looted and used to enrich others, while her children go to sleep on empty stomachs (and invisible), as the key to our freedom. It’s hard to choose yourself when you’ve only known yourself a slave.

Alice Mann

Born in 1991 in Cape Town, South Africa. Lives in London, United Kingdom

www.alicemann.co.za | instagram

Drummies, 2017

These images depict the unique and aspirational subculture surrounding all-female teams of drum majorettes in South Africa. These girls, affectionately known as ‘drummies’ are from some of the country’s most marginalised communities.

For the girls and young women involved, being a drummie is a privilege and an achievement, indicative of success on and off the field. It gives them a positive focus and sense of belonging, providing them with structure in a community where opportunities are often severely limited. As a female only sport, ‘drummies’ is a safe space where the girls are encouraged to excel, and their distinctive uniforms serve as a visual marker of success and emancipation from their surroundings.

With my continued investigation into this subculture, I hope that these images can communicate the pride and confidence these girls have achieved through identifying as ‘drummies,’ in a context where they face many social challenges.

Xoliswa Ngwenya

Born in 1990 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Soweto, South Africa

thatguyxoliswa.tumblr.com | instagram | twitter

In my solitude, 2018

In my body of work I’m documenting the coal yards in Zola 2, Soweto, looking at how the residents relate to the space they occupy. This is a place that gives them the sense of home, as many are away from their actual homes due to certain circumstances and reasons that I will be also investigating in this photographic series.Coal yards are one of the historic places in the township, and were built by the Apartheid government between 1956 – 1963 after the forceful removals of black South Africans who lived in places such as Brickfields (now known as Newtown) Sophiatown and Alexandra. In the early days of Soweto, electricity was not available so coals were essential for domestic and commercial use. The government of that time saw a great opportunity to make profit from this need by building the yard to store coal and also employ the members of the community; later, the community members gained full right to sell and distribute coal within and around Soweto. In this series, I’m exploring themes such as displacement, belonging, reflection, relation, masculinity, solitude and identity. The community kept on warning me about passing the coal yards alone,people who stayed there were heartless criminals. They labelled the coal-yard dwellers as thugs, drug addicts and hooligans.My curiosity about these vilified persons led me to start this project. I wanted to understand their alleged difference from the rest of the community, why the community chose to treat them as ‘subhuman’, a tag I learned from my conversations with Sibusiso, a coal yard resident, when we first met. I became interested in knowing more about them and the place they live in, and saw my body of photographs as an opportunity to stop this stereotyping. Thus, my project has a strong dimension of social awareness, and comments on the social and political realities which these people face. This body of work is also a continuation of my previous work, but now I’m also looking at the emotional wellbeing of these characters, trying to unpack the issue of mental health and toxic masculinity in that space.

Frederic Noy

Born in 1965 in Beauvais, France. Lives in Kampala, Uganda

www.fredericnoy.com | instagram | twitter

Inside wakaliwood: uganda's action movie studio, 2017–2018

In Wakaliga slum, Isaac Nabwana has put Uganda on the cinematic map by shooting, in his courtyard, $200 action comedies packed with helicopter raids, kung fu, zombies and collective spirit.

Wakaliwood, a man’s passion become reality against all odds, offers the story of a human condition, where the consciousness of the absurd walks side by side with the certainty of being able to triumph over a destiny that promised very little, in any case no cinema.

The dream of Nabwana relied on the vocation of his brother Robert who discovered Kung Fu in Bruce Lee's films, thirty years ago. Mimicking them, he inoculated to Isaac the cinema virus while contracting the martial arts’. Isaac understood then that his destiny was cinema. The universal dimension of Wakaliwood lies in the alchemy linking Luther King to Nietzsche, "I had a dream" to "Become who you are».

Death, gunshots, victims dying in blood-red geysers are an echo of Isaac’s childhood. A time when innocence did not prevail in Kampala in the 70s. Idi Amin ruled summoning to the parlor of history fear and murders. Nabwana has not forgotten the swollen corpses discovered in a dump closed to his home nor the soldiers’ raid, nor Bruce Lee… From the magma mixing reality and memory, emerged a unique creator who tells contemporary Uganda. Not the real society, but the one that the commuters feel. Filled with latent violence, garnished, supreme elegance, with humor.

The ingredients of Wakaliwood: laughter that allows to cross without affectation, difficult situations. And violence, not Ultra but Meta. This Greek prefix meaning after, beyond, poses what violence is in Wakaliwood's production. Not an end in itself, but a vector to transcend, a grammar that does not give meaning but style, a mirror in which the Ugandan society self-reflects with irony.

For more than 3 years, I explore the world of a pop-culture prophet who preaches from his studio-shantytown, the good word of the 7th art, not to win the heart of some distant moviegoers but to leave a footprint. We always discover ourselves dwarf when surfing on Wakaliwood’s wave.

Joseph Obanubi

Born in 1994 in Lagos, Nigeria. Lives in Lagos, Nigeria

www.behance.net/josephobanubi | instagram

Techno heads, 2018

This series explores how individuals within the contemporary African society navigate through day-to-day patterns of life, infiltrated with technology, even in its simplest form. With advancements in mechanization, there has been a seismic shift in the way ideas, thoughts and information are proliferated amongst people; there is more reliance and dependability on the dynamic spectrum of technological devices available, such that existence without these is seemingly unthinkable. The contemporary society strongly revolves around and depends on technology for communication, motion, and navigation, all of which are central aspects of human existence.

Figments of this revolution are portrayed within each of the works in this series, as part of a being, swapping naturally occurring forms of the subjects with an infusion of mechanised forms, projecting the idea of a techno-utopia. The series also dabbles into Metaphysics in the African context, exploring how identity, space and time have become intricately linked with even the simplest products of technology. It seeks to merge African metaphysics and (simple) technology to explain alter reality and how they portray techniques and concepts of freedom for Africans in the contemporary society. This merger of both factors allow the observer to discern just how intertwined technology and humanity have become, challenging them to ponder into this, as it affects each member of the contemporary society.

Brian Otieno

Born in 1993 in Nairobi, Kenya. Lives in Nairobi, Kenya

www.storitellah.com | instagram | twitter

Kibera: stories from within, 2016–2018

Kibera, where I was born and raised, is a vast slum settlement located in Nairobi, Kenya. It is said to be home to between 350,000 and 1 million people, depending on who you ask. This has given rise to its reputation as “the largest slum in Africa”. But behind these vague statistics, Kibera has thousands of stories to be told.

From afar the neighbourhood is a dense jungle of rundown corrugated rooftops, indistinguishable huts huddled closely together with TV antennas and electricity poles projecting into the air. While Kibera is hardly a continuous cycle of poverty and hardship, that has always been the dominant visual narrative.

But within its ever-sprawling and captivating landscapes, Kibera is a mix of diversity, vibrancy and great capabilities. This project presents life in Kibera from a socio-economic, cultural, political and environmental point of view, as seen from an insider’s perspective.

Through these images, we see and feel dynamic moments of everyday life, identity, and individuality, and the uniqueness of representation in moments always seen but often ignored or unnoticed.

Samantha Reinders

Born in 1977 in Cape Town, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

www.samreinders.com | instagram | twitter

The land that begins again, 2017–2018

It’s been said that wherever you go becomes a part of you somehow. I would argue that who you are leads you to certain places…For me this could be said about the Karoo.

The semi-desert folds of the Karoo stretch over five degrees of longitude of South Africa. Swaths of arid, dusty and desolate land that to the naked eye looks like nothing, but with the right tilt of the head is teeming with life and vibrancy. There are a few scattered towns and the country’s main highway that conveniently and quickly escorts people through it without stopping.

Four generations ago though my ancestors stopped and made a life here. They, like I do now, recognize the incredible beauty of this nothingness.

The Land That Begins Again is a love letter, of sorts, to that place of dust and dreams. It’s an exploration of my self, past and present, in a geography that is at once universal and at the same time so uniquely South African it is not possible to separate it’s DNA (or mine) from its physical place on a map or its specific existence in a time in history.

The final presentation of this work includes items – collected from the Karoo – which will be exhibited alongside the images.

Rijasolo

Born in 1973 in Strasbourg, France. Lives in Antananarivo, Madagascar

www.rijasolo.com | instagram | twitter

Perception of authority in rural areas in madagascar, 2015–2016

I photographed the people who represent the Authority in the rural world: the man of the church, the gendarme, the district chief (local representative of the State), the local king, the chief Fokontany, the mayor, the "raiamandreny", the traditional doctor, etc.

These people with an "authoritarian" function in the bush have almost absolute power among the rural population. This power is granted either by the people (election), or by the State, or by the Tradition.

This power may be misused by its holder who may exploit it in his personal interest. These practices are encouraged by the apathy of the rural population, most often illiterate (in 2014, 46% of Malagasy could neither read nor write according to the Ministry of National Education) and in constant economic and food survival; apathy also accentuated by the prevailing political discourse affirming that "fatality" is the cause of Malagasy problems. Thus the idea of demanding an improvement of the daily life or of holding these representatives of the Authority accountable is not even (any more) envisaged. This mentality has been passed down from generation to generation and has become a general pattern of thought among the majority of Madagascar's inhabitants. This traditional form can take the name of "fihavanana", which can mean solidarity, but in a broader sense, can mean "spirit of moderation". The fihavanana is a typical Malagasy way of approaching human relations on the Big Island, and is a way of "maintaining social balance" in Madagascar. But as the writer Johary RAVALOSON says, the fihavanana can be a way of enslaving the poorest and least educated against those who hold power, the Authority, thus making it possible to annihilate any contesting project.

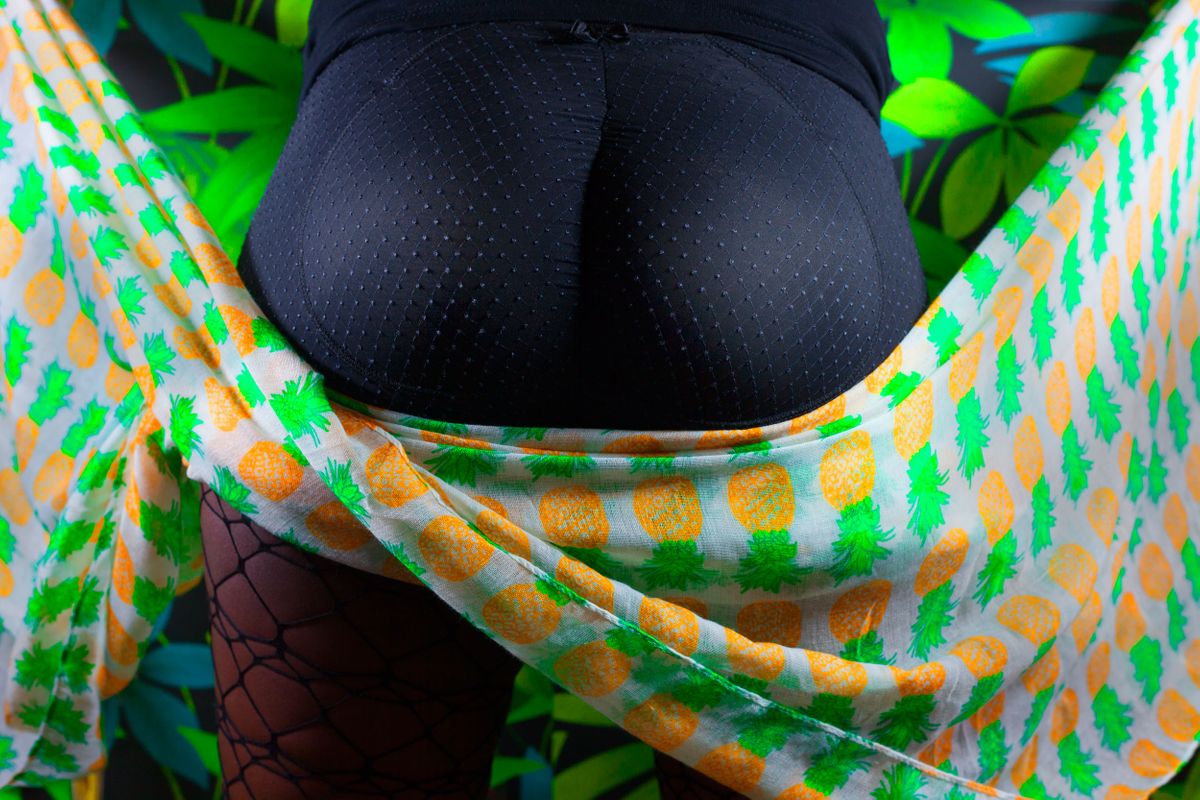

In the process of reflecting on post-colonialism in western societies, what is left of the sexual projections on enslaved or colonized female bodies?

Once materialized, animalized, turned exotic, erotic, these women, held under physical and mental domination, are the symbol of violence which constrains bodies.

All we are left with are archived images as witnesses of a period in our common History. These projections laid deep scars on the bodies of black women, scars cut open yet again through the advertising images.

The fantasy around a black woman’s body to be conquered is very often paired with desire for nourishment. The fantasy is evermore flagrant in taboo-free anonymous forum discussions on the Internet.

An initiative has put me in the shoes of this “object” of projection, and with the intervention of an image, with the goal to visualize that which was not possible to see on “the other”.

The words were stumbled upon as I researched french forum discussions, and they finally created a sort of a 2.0 bad taste poem.

Abdo Shanan

Born in 1982 in Oran, Algeria. Lives in Algiers, Algeria

www.collective220.net | instagram | twitter

Dry, 2017–2018

How is it possible for an island to exist in the middle of an ocean? Is it because the island’s dry soil is strong enough to impose itself against the ocean, or is it that the merciful ocean tolerates the existence of the island? Maybe it is a relationship of compromise where both sides slightly renounce their claims in order to co-exist.

I was born in Algeria to a Sudanese father and Algerian mother. Am I an island? Where is my ocean? What is my relation to it?

How can an environment influence our identity? Between the land where we live and the lands that we have history with, where and how can we identify ourselves? This project questions the relationship between humans and the environments where they live (or have lived). How identity is shaped and how they define the concept of “home”. ‘Dry’ is a photo-essay that has Algeria as a common environment between subjects from different races and nationalities.

Molebogeng Thoka

Born in 1996 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Midrand, South Africa

lebothoka.wixsite.com | instagram | twitter

It is well: an ode to karabo, 2017

This body of work is inspired by Karabo Mokoena, a 22 year old God fearing young woman who was the victim of abuse at the hands of her partner and who was brutally murdered and her body burned beyond recognition in a shallow grave. She, like many women in this country have been failed by a society and a justice system that does not prioritize the violence women face in the hands of abusive men on a daily basis.

This body of work is a self-portrait photographic series that aims to document various stories of South African women across economic backgrounds,ethnicities & races who have fallen victim to the scourge of Femicide in South Africa. The body of work incorporates a mainly conceptual photographic approach in each portrait. Each title of each portrait in the series is the name of the deceased woman, & the description has each woman’s age as well as the events that led to each woman’s demise.

The South African justice system does not prioritise the protection of women when it is necessary, but only when it is beneficiary to it. Patriarchy is the puppeteer and women are its puppets.

Men have failed us. South Africa has failed us.

Despite the overwhelming violence we face,women are not defined by the violence that cloaks us. We are not defined by the failures of the South African justice system. We are not the cloth that men wipe their mistakes onto and discard. We will not be defined by a society that fuels its engines with our blood and props itself up with our bones.

We are the sum of the power and potential that society tries so hard to beat out of us. We might bend but we will never break.

We will overcome.

Jansen van Staden

Born in 1986 in Potchefstroom, South Africa. Lives in Cape Town, South Africa

instagram

Microlight, 2015–2018

After the death of my father in 2011, I discovered a letter, written to his psychotherapist, about his time in the Border War. He dedicated his life to sustainable projects and education in African countries, and what I read in the letter took me by surprise. It was not the man I knew. The letter detailed horrific incidents he took part in, as a 17 year old boy.

One paragraph from the letter, bothered me the most: "...she stated that I joined and did what I did, because I wanted to kill people. It is truer than true"

Questions started harassing me. How was he raised? What influence did the apartheid regime and it's ideologies, have on the family? What circumstances could lead a 17 year old boy, to have such murderous intent? Where does all this violence stem from?

Through this journey, I discovered just how much my life has been influenced by my fathers' trauma. How my fathers' siblings are still affected by the ideologies of their father. Generations of trauma, ignorantly passed on, even through our genes. My generation, is the first of South Africans not to experience war. We have the opportunity and the responsibility to observe all this within ourselves. To ensure that it does not continue.

After the war, my father turned against everything the knew. He left his father, and family. He craved resolve. He wanted so badly, to be free from his shadows. But the consequences of his actions haunted him his whole life. He tried his best to keep it from his children, and his wives. Ultimately, it slipped though the cracks.

Microlight is a collection of anecdotes. And through telling these stories, I hope to open this discussion. I yearn for healing. I want to understand, so that I can accept, and move on.

John Wessels

Born in 1987 in Johannesburg, South Africa. Lives in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic Of The Congo

johnwessels.photoshelter.com | instagram | twitter

Kinshasa, drc – the road to elections, 2018

In west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 13 million souls live at the forefront of the struggle for normality: pushed between the banks of the Congo River within the congested, smoke-filled streets of Kinshasa. Since the end of Joseph Kabila's presidential mandate on the 19th December 2016, thousands took to the streets of the capital in renewed protests, demanding Kabila’s resignation. In more recent occasions, protesters have been killed and thousands of voices silenced. By the time 2018 came around promises were made to the people of DRC that on the 30th of December 2018 they would be able to line up and cast their votes. On the 24th of January 2019, Felix Tshisekedi, leader of the main opposition party was sworn in as President. A confused felling of relief filled Kinshasa. By no means was this perfect elections, but the first steps have been taken.

Etinosa Yvonne

Born in 1989 in Nigeria. Lives Abuja, Nigeria

www.etinosayvonne.me | instagram | twitter

It's all in my head, 2018

It’s All In My Head is a multimedia project that explores the coping mechanisms of survivors of terrorism and violent conflict by using layered portraits of the things they do to help them move forward or otherwise.

The project aims to advocate for increased access to psychosocial support for the survivors which in turn will improve their mental health.

In the last twenty years, Nigeria has witnessed an increase in terrorism and violent conflicts. Some of these survivors have witnessed the most violent acts been meted out on them, their loved ones and in some cases all that they own.

It is interesting to know that while these survivors find a way to rebuild and adjust to their new lives, many of them never get to talk about their experiences. Thus, the idea of "moving on” can be considered to be a charade as they are stuck in the past while trying to start over.

Exploring the coping mechanisms of these individuals gives an insight to how these survivors struggle to move on amidst little or no psychosocial support.

The motion, still images and sound all play a significant role in showcasing how the survivors cope or feel.